Today’s post comes from Chris Dietz, class of 2017 and Art Center Student Docent.

(German, 1471-1528)

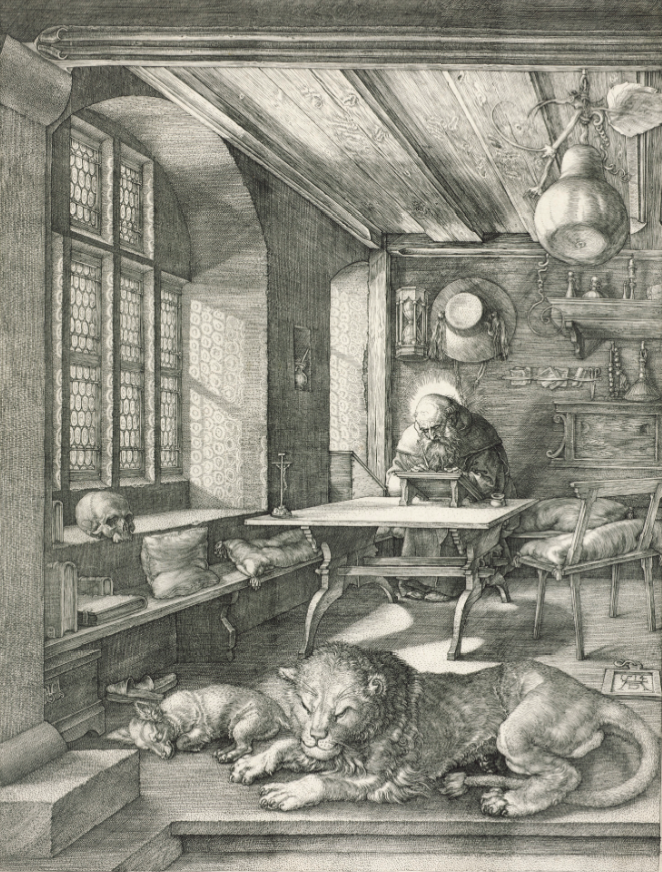

St. Jerome in His Study, 1514

Engraving on cream laid paper

Gift of Mrs. Felix M. Warburg and her children 1941.1.25

The Art Center’s delightful new exhibition, Mastering Light: From the Natural to the Artificial, showcases one of the most interesting works in the permanent collection—the German master Albrecht Dürer’s St. Jerome in His Study.

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) was arguably the greatest artist of the Northern Renaissance—an engraver and printmaker foremost, he also launched extensive forays into painting and mathematics, notably utilizing watercolor to paint landscape, as well as publishing theoretical treatises on perspective and proportion. His beautifully intricate woodcuts and copper engravings are his calling cards, as their attention to detail and use of motifs from classical antiquity represented a peak both of his own personal achievement as well as of the High Renaissance period. Given the challenges of the print-making medium—the engraving instrument, the burin, resembles a sharp letter opener with a doorknob on the end, a far cry from a paint brush— Dürer’s deft intricacy is impressive.

St. Jerome in his Study is one of Dürer’s most critically acclaimed and well-known works, an engraving that stands among the most ambitious of his prints. The central figure is St. Jerome, a fourth century scholar who translated the bible from the original Hebrew and Greek into everyday Latin (his new text was referred to as the Vulgate). Dürer has transplanted St. Jerome into a fifteenth century room, perhaps the personal study in Dürer’s own home. Symbols include the lion, part of St. Jerome’s iconography, as well as a dog, which Dürer often painted to symbolize loyalty. A cross is situated on the left of the desk, and a skull lies on the windowsill. As in many depictions of St. Jerome, there is a nod to the contemplative life—life spent with an awareness and comprehension of our earthly transience. Dürer chooses to elaborate this motif by connecting Jerome, the cross, and the skull through perspective—if you were to draw a line from Jerome’s head to the skull, it would not only pass through the cross, but the angle would match the correct angle of perspective!

Dürer’s room is also an absolute clinic in terms of depicting light (which is why it plays a prominent role in the exhibition). Light plays fancifully through the windowpanes, creating distorted shadows on the walls. Light careens off the tables, animals, and ceiling, casting a gentle darkness on the floor and crevices. In this scene, Dürer is concerned with the brilliance of the naturally illuminated space—even in the darkness of the shadows there isn’t much darkness, as if to imply that scholarly work such as St. Jerome’s is not done in some murky dungeon, but is instead always sanctioned by the light of the world. The purest light in the room, though, is St. Jerome’s halo, hinting at the divine inspiration that fills St. Jerome as he works. Divine inspiration is a mystical experience, and Dürer notes this by disallowing the halo to interact with the outside world—St. Jerome’s shadow is engraved as though the halo isn’t there at all. Marking the difference between natural light and divine light is another acknowledgment of transience, of the disparity between this world and the next.

There is a subtle irony that underscores St. Jerome and its fellow works on paper in the Mastering Light exhibition: the light that the prints depict and create can also destroy them, in a physical sense. Because of the composition of paper and ink, works on paper are much more susceptible to fading and damage from light than paintings are. To observe St. Jerome in person is a real treat, as the print can’t be displayed often, or for too long. One might say that this condition is another reminder of transience: the work itself, like people, can’t exist forever in this world. In other words, check it out while you can!