Today’s post comes from Alison Dillulio, class of 2013 and Art Center Student Docent.

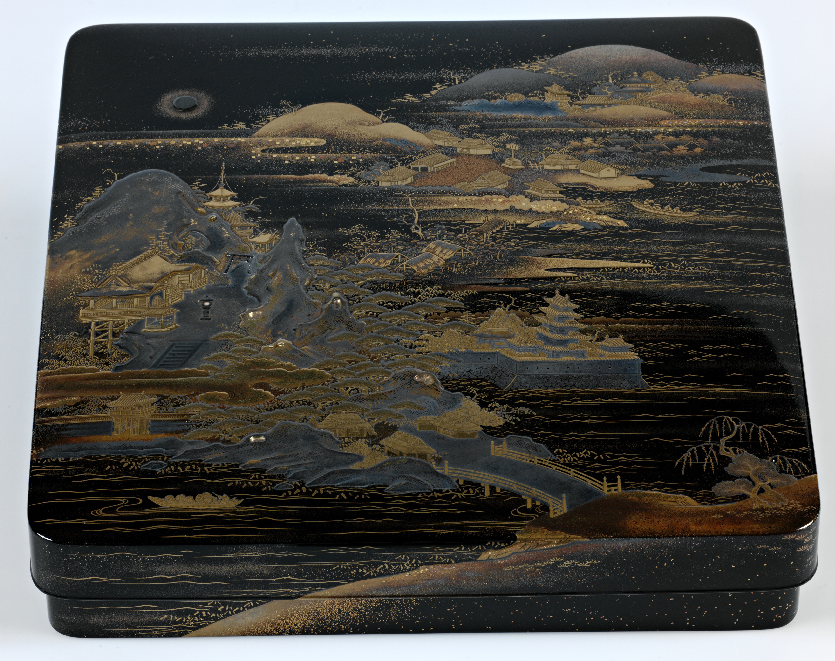

Unknown [Japanese Mid-to-late Edo period (1615-1868)], Inkstone Box (Suzuribako) with Eight Views of Omi (Omi-hakkei). Wood coated with lacquer and gold. Purchase, Pratt Fund. 2008.21.

The suzuribako is one of many Asian art objects in Vassar’s Francis Lehman Loeb Art Center collection. It is not currently on view.[1] However, by discussing the work and illuminating its impressive qualities, I hope to metaphorically unearth it from our vault. The suzuribako is an elaborately decorated lacquer object dating from the Edo period in Japan—a time of economic and cultural prosperity and a moment in the history of Japanese lacquer in which design was most intricate and daring in its combination of several media.

The suzuribako is a writing box intended to store the implements necessary for the Japanese art of calligraphy. It contains an ink stone (suzuri), above which lies a water dropper (mizu-ire), and an adjacent removable tray which would have stored the artist’s brush (fude) and ink stick (sumi). The artist would have removed the highly decorated lid and placed it facedown before him so he might admire the equally intricate design covering the interior surface of the lid. He then would have released a few drops of water from the water dropper onto the surface of the inkstone, ground an ink stick against the inkstone to release the pigment using a sliding technique, and then dipped his brush into the moistened ink and applied it to a sheet of paper.

The lacquer design portrays a common Japanese subject, the Eight Views of Omi (Omi-hakkei), which were originally a series of eight Japanese poems describing the eight views from the Lake Biwa area of the Shiga Prefecture, a region near Kyoto. The selection of eight, commonly represented in Japan, is in turn based on the well-known Chinese poems and paintings of the Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers, which inspired several Japanese adaptions both in poetry and in the visual arts.[2] Ando Hiroshige’s Omi hakkei series of eight prints (1834), four of which reside in the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center’s collection, is a better-known, later example of the ongoing Japanese tradition of artistic depictions of this same subject matter.

The writing box appears in immaculate condition, as a result of the durable, waterproof layers of lacquer between which the design lies suspended. The lacquer used to coat this box is a form of purified sap (urushi) collected from the Rhus verniciflua tree, of the same family as poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac. The sap must go through multiple extraordinarily intricate purification processes before it may be applied to an object. In its raw form the sap is extremely toxic if inhaled and can cause a severe rash if it touches exposed skin. Craftsmen exposed themselves to small amounts of the sap at a time in order to build their tolerance against such reactions. Once the purified sap has been applied to an object, it does not “dry” but instead must harden in storing containers kept at high humidity for several hours after each of its numerous thin coats have been applied.

The danger of working with a toxic material such as urushi and the intricacy of its elaborate purification and application process make our suzuribako an astounding piece of craftsmanship, one that remains far more impressive than modern examples that benefit from modern technology and disregard the lacquer tradition. Our suzuribako is a true example of the art of lacquer—an art deeply ingrained within Japanese cultural history.