Today’s post comes from Annie Massa, Vassar College class of 2013, and Art Center student docent.

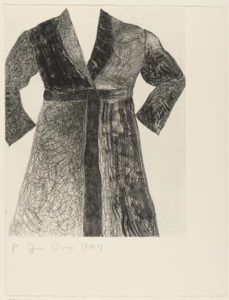

Be honest. When you approach a black and white print hanging in a gallery (like Albrecht Dürer’s exquisite Adam and Eve from the Art Center collection), don’t you get the tiniest urge to just… break out a pack of Crayolas and color it in?

The Art Center docents do, at least. And we’ll finally get to indulge that urge at tomorrow’s Late Night Leaves the Lehman Loeb. In a low-key, stress-free study break environment, every Late Nighter will receive (drumroll, please) a limited edition Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center coloring book! At last, the opportunity to color Eve’s hair magenta and to draw an anchor tattoo on Adam’s muscular upper body.

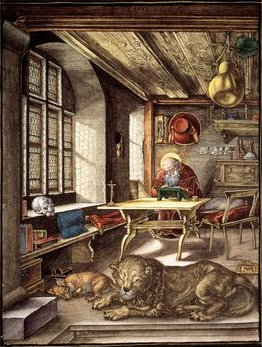

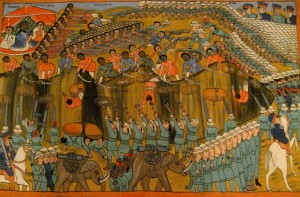

Don’t be too scandalized by our behavior. Though today Dürer prints rarely exist in anything but black and white, adding color to prints was actually quite commonplace in Northern Europe from the 15th-17th centuries. Colorists were known as Briefmaler, and their work was on par with that of the most distinguished manuscript illuminists. When a block cutter made an engraving, he fully acknowledged that prints of his image would be colored in a workshop— some pieces couldn’t even be considered complete without certain crucial touches of color. Take, for example, the National Gallery’s Christ on the Cross with Angels, c. 1465-75. Three angels wielding chalices are positioned at Christ’s hands, feet, and side, intending to catch the blood dripping from his wounds. The original print design for this piece doesn’t outline the blood at all; rather, a colorist had to lay in red paint to finish the print and express the composition’s full meaning.

A print colorist would sometimes even initial his finished product in gold paint, indicating that Briefmaler took great pride in their work, and that patrons recognized them by name. Archival evidence suggests that the value of a print would go up after it was colored.

So, why don’t we see more colored Renaissance prints in galleries today? The devaluation of colored prints began with humanist and theologian Desiderius Erasmus and his 1528 Dialogues. In highlighting Dürer’s mastery of engraving, Erasmus insisted that lesser artists only applied color to their prints in order to make up for inadequacies in technique. Using cross-hatching and fine-hatching, Dürer could achieve the effects of light, volume, and even varying tones that had previously only been possible to portray in color. In Erasmus’ eyes, Dürer had ushered in a higher class of print design, which he celebrated for its colorlessness. This was an artist a cut above the rest.

The truth is, however, that most Renaissance and baroque art forms are richly colorful—think stained glass windows, frescoes, devotionals, and tapestries. Against all those other colorful media, don’t you think Adam and Eve feel a little naked? Join us tomorrow to color them in. To read more about Renaissance-era colored printmaking, be sure to check out Susan Dackerman’s exhibition catalog, Painted Prints: The Revelation of Color in Northern Renaissance & Baroque Engravings, Etchings & Woodcuts.