At the conclusion of World War I, Germany suffered terrible financial and social backlash from the rest of Europe. Veterans and civilians alike struggled to pick up the pieces and move on from wartime. War profiteers in Berlin lived sumptuously, in high contrast with the wounded veterans and families who outlived their primary breadwinner. Impoverished wounded veterans and war widows struggled to make ends meet and were shunned as a constant reminder of Germany’s humiliating defeat and terms of surrender.

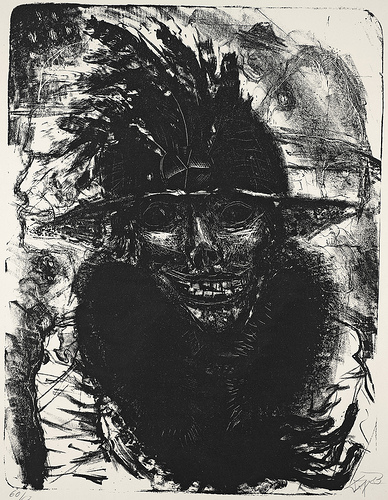

Otto Dix, a German artist working out of Dresden and then Düsseldorf, depicted this culture of the defeated in post-war Germany. A prime example of his work in this vein, Nocturnal Apparition, can now be seen in the Art Center’s exhibition Recent Acquisitions: Works on Paper (through March 30). In Nocturnal Apparition, a lithograph from 1923, Dix depicts a skeletal prostitute, leering out from the paper and smiling diabolically at the viewer. Her thick fur stole and feathered hat contrast with her bony face. The skeletal features are emphasized by the intense and stiff highlights on her cheeks and nose, by the broad smile that reveals uneven teeth between her thin lips, and by large black eyes more reminiscent of the voids of a skull than of eyeballs. She is backed by an ambiguous setting of shadowy figures and wavering forms, neither here nor there.

Nocturnal Apparition condenses the social and economic state of Germany after World War I into a symbol representing the conflicting poverty and decadence. The poor, especially women who lost their financial support, and wounded veterans lead depraved lives that cater to the wealthy, who despise them as remnants of the devastating war and wretched, debased people. Nocturnal Apparition may also have played into the fears of syphilis that pervaded European society, with the subject as a reaper in disguise, having shed the robe and sickle for a feathered hat and beguiling smile.

Behind her swirl the faces of men; one is even a self-portrait of the artist in profile. The faces serve to reinforce the prostitute’s position in society as subject to their desires, desperate for their money—and maybe the eventual agent of their death. She is despised by society for her shameful profession and the circumstances of war that led her there, but she is also used by those above her. Through this frightening and tragic conception of the plight of the German people, Dix comments harshly on the degraded German society that produced her.