Today’s post comes from Tara Peterson, Vassar class of 2025 and Art Center student docent.

For the several months at the Loeb, two exhibitions have been the main attraction to most visitors, especially those partaking in our daily tours at two o’clock. Mastery and Merit: Tibetan Art from the Jack Shear Collection and Beyond the Threshold: Tibetan Contemporary Art, which are not a part of the Jack Shear Collection. The exhibitions were curated side-by-side in hopes of illuminating the different forms of Tibetan culture, both traditional and contemporary. The first focuses on various religious Buddhist artifacts, complementary to the latter, which is composed solely of contemporary Tibetan works.

The exhibitions were precipitated by a joint acquisition made by Jack Shear, collector and Executive Director of the Ellsworth Kelly Foundation, which included Tibetan thangkas and objects shared between Vassar College, Skidmore College, and Williams College.

Acquiring Tibetan religious artifacts for conservation has been a habit of some collectors for many years since the occupation of Tibet began in 1959, which saw the destruction of many Tibetan monasteries and artifacts. Thangkas, which comprise a majority of the donation and exhibition, are a traditional art form in Tibetan Buddhism. They were originally produced by monks for temples, and later evolved into an artisanal craft done by trained artists. Thangkas eventually found their place in the home and were often done by commission, depicting scenes and stories from Buddhist scripture as a form of educational tool as well as devotional object. Although often used by casual practitioners, many thangkas exist as forbidden or hidden objects, which are only available to be seen by higher trained monks and practitioners. These objects are commonly thought to be a danger to the journeys of practitioners too early in their tracks towards enlightenment and must thus be kept hidden until the time when the student is ready to witness them.

Whereas thangka making is an ancient and continuous practice in Tibet, contemporary artworks are a relatively new development—the Chinese government has only begun relaxing laws on artistic production in the region in the last thirty years. Contemporary Tibetan art began being displayed in galleries in the early 2000s at museums such as the Bowers Museum of Art and Columbus Museum of Art. The genre quickly gained popularity. Even then, many Tibetan artists, including some of those featured in Beyond the Threshold, live and work outside of their home country.

Despite their removal from the practices of Tibetan Buddhism, these contemporary works do not lose all connection to their native religion. Many works in the exhibition feature works that pull inspiration from traditional thangkas, such as the inclusion of a central religious figure surrounded by illustrious backgrounds. One of them is Mahakala by Gade, which features, and is named after, a Buddhist deity that is said to take on the form of absolute reality. In this case, Gade illustrates said reality as violent and disturbing.

Another artist featured in the exhibit, Tsherin Sherpa, was trained to create thangkas by his father. In an essay he wrote for Anonymous, an exhibition featuring his work at the Dorsky Museum in 2013, Tsherin describes his evolving relationship with the craft. Over the course of his family’s dedication to it, the craft changed from a highly respected art form toward lesser value in a matter of decades. He wrote that the use of his family trade in his work demonstrates the Tibetan struggle with identity in modern society, which in his words “seemed inseparable from Buddhist thought, yet at the same time was so intermixed with foreign cultural materials that we find ourselves around in exile…” Sherpa goes on to describe the lack of non-traditional art he encountered as a young person in Tibet. The invention of new art forms was seemingly disrupted as young people entered British Catholic schools or joined monasteries, both which valued traditional practices.

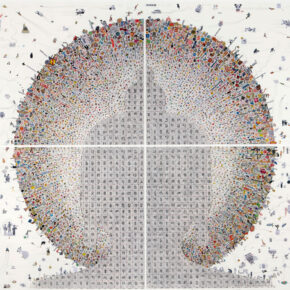

Other items in Beyond the Threshold, such as works by Gonkar Gyatso as well as one by Dedron, feature prominent nods to Western media and consumerist culture. Dedron’s Mona Lisa and Gongkar’s Daily Doodles (featured in our In the Spotlight series and the Old Bookstore) both show popular characters from Western imagination, including a modern take on Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, and in Gyatso’s doodles are other figures from popular Western culture like Santa Claus and Snow White. A different work by Gyatso in the gallery, titled The Shambala of Modern Times, shows a large figure with the appearance of Buddha surrounded by a halo consisting of modern logos and advertisements, exploring the relationship between consumerism and religion.

Visitors who have seen the exhibitions vary from students of Buddhist art, to those without any experience with the culture and one visitor who shook the Dalai Lamas’ hand. It’s needless to say that both exhibitions have gained a healthy audience of curious onlookers. The exhibitions are scheduled to remain at the Loeb through July 31.