Today’s post comes from Julie MacDonald, Class of 2012 and Art Center Student Docent.

On February 16th, professor Ismail Rashid brought students from his Modern African History (HIST/AFRS 272) class into storage here at the Art Center to view a variety of objects that not only address issues in African history, but also African art and the way it is handled by institutions like the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center. The course addresses the political, economic, social, and intellectual movements that have defined African experience from the early 19th century to today, through a variety of perspectives including trade relationships and diplomacy. Particular attention is paid to the way in which Africa acted on the global stage, especially before the dominating presence of European imperialism. Objects from the museum’s collection enhanced the course’s aim to track the rise of independence and African nationalism and how such cultural shifts are exhibited in the work of African artists.

Diane Butler, the Andrew W. Mellon Coordinator of Academic Programs, first brought the group to view a collection of 140 West African masks that raised questions of authenticity and highlighted a positive cultural exchange between Africa and Europe. These objects were produced in the 20th century solely for export to Europe and were not used in a traditional African context, representing an unusual relationship in the face of colonial imperialism. Ms. Butler emphasized the role of the Art Center in assessing such objects for display, noting that while they were crafted in an authentic style, they are too heavy to actually have been worn in a masquerade—revealing their made-for-export origin.

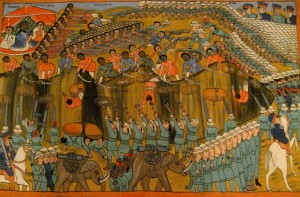

The second set of objects further questioned the role of the art institution as a steward of cultural artifacts. Upon considering two Ethiopian paintings, it was instantly clear that these works were not created in the Western art tradition, as the canvases were not stretched onto a wooden frame, and instead would have been simply tacked onto a wall for display. In displaying these works, the Art Center took care to respect the authenticity of display while still protecting the object from damage. The Ethiopian paintings were also interesting to consider in a historic context, as they offered an admiring representation of an extremely divisive political figure during the unification of Ethiopia.

Finally, a set of photographs from 1964 and 1965 powerfully exemplified a historic moment in Africa. The photographs, taken by Malian photographer Malick Sidibé, depicted young men and women dancing in celebration of the dawning of a new, modern, and independent Africa. They serve as a reminder to break stereotypes of what is expected from “African art” and of the power of photography to capture and record the atmosphere and feeling of a moment.