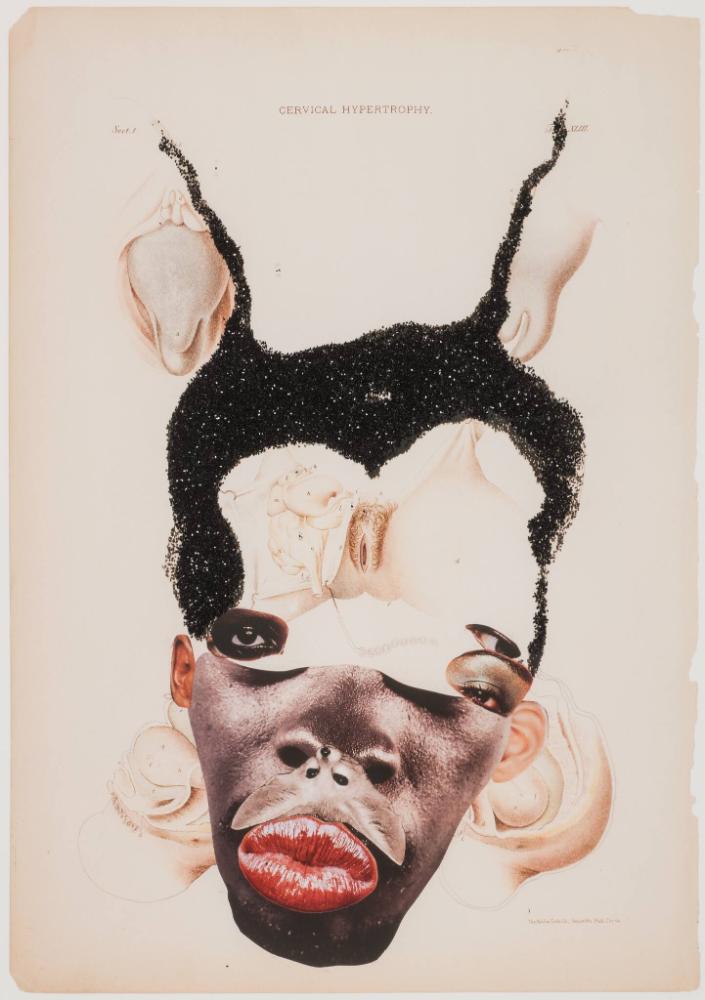

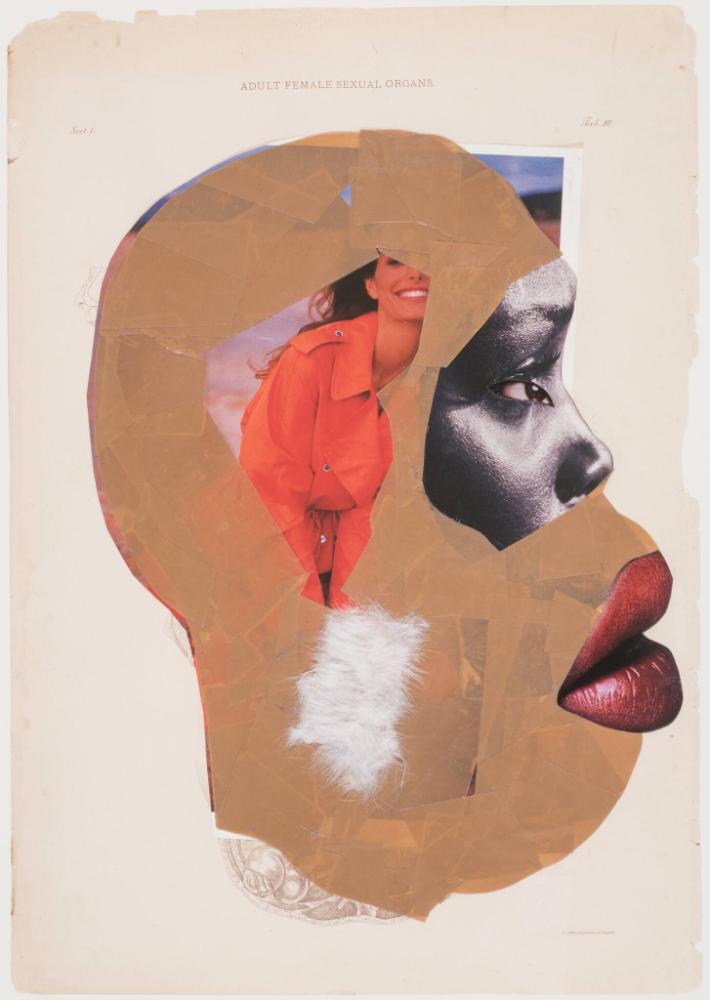

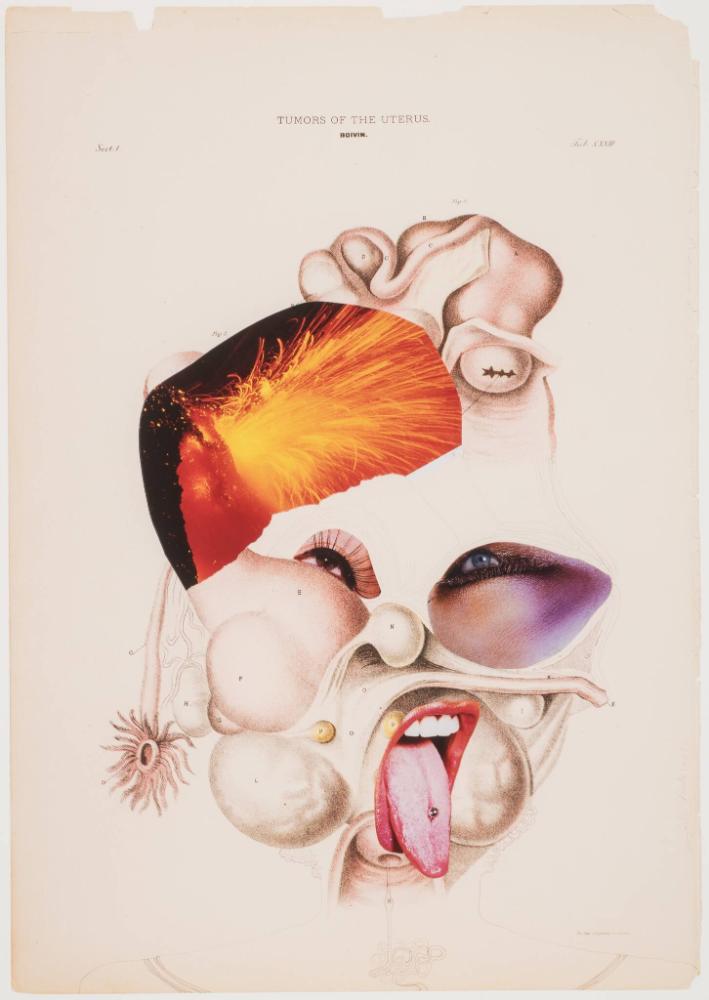

Reflecting on Women’s Health as a theme for this year’s Women’s History Month, I knew I wanted to focus on the intersections of women represented through art. After being introduced to Wangechi Mutu’s piece Histology of the Different Classes of Uterine Tumors, I was extremely moved by the intricacies of its meaning. This work is a series of twelve mixed-media collages that each borrow and comment on medical representations of uterine diseases. Subsequently, these collages question the impact of sociological perceptions of women and people with uteruses in medicine.

The images that Mutu reappropriated are originally from extremely reductive representations regarding women and uterine health included in medical folios. I became interested in the piece because I have personally noticed the vast underrepresentation of information regarding women’s health (and specifically reproductive health) in my own biology-centered classes. When the issues regarding women’s health are addressed, they lack a humanistic approach, boiling down a woman’s body to the organs affected and impersonal statements regarding women’s hormone cycles. This view on women’s health is deterministic, and doesn’t take the person behind the organs into account. Moreover, these medical journals contribute to the vast underrepresentation of women of color, and specifically black women in medicine.

Mutu’s work calls for the critical analysis of prevailing anthropological paradigms and their continued impact on the intersecting identities of women of color today. Through the superimposition of fragmented and collaged pornographic and ethnographic images onto antiquated representations of disease, Mutu has created exaggerated abstracted images of Black women’s faces. The stark contrast inherently created through mixing these mediums challenges viewers to confront and humanize the images being presented to them.

Wangechi Mutu intended to comment on the dehumanization of women in medical illustration with the impassive title and use of twelve medical folios from the nineteenth century. The title reads like a heading in a medical journal, setting the reader up to expect the typical images of organs—used as source material in this piece—to describe women’s disease. The repetition of the twelve pieces takes viewers through the journey of humanizing the pictures. In an overwhelming exploration of color and texture, Mutu subverts any preconceived notions that viewers might have held about the diagnostics regarding uterine diseases.

The meaning of this piece can be extended to the vast reduction of many classes of diseases, for the sake of standardization in medicine. However, I believe Wangechi Mutu’s focus on uterine diseases calls into question the vast oversimplification of the female body in medical literature. I believe this is a way virtually every culture can perpetuate the hyper-policing of the female body. The withholding of information about their bodies strips women of the power to have agency over them in a patriarchal society. In Mutu’s words: “Females carry the marks, language, and nuances of their culture more than the male. Anything that is desired or despised is always placed on the female body.”

While Mutu doesn’t directly address the other intersections that exist between women, she inherently challenges viewers to critically examine how the female body is viewed in the literature. The vast underrepresentation of women of color, trans women and men, and those whose identities intersect these categories is directly correlated to their ostracization within the medical community. Mutu undermines hegemonic medical models by asking: What is it that we treat; the person or the disease?