Today’s post comes from Ian Shelley, Vassar class of 2022 and Art Center student docent.

One of the most conspicuous expressions of colonialism in Western art has been Orientalism, a nineteenth-century movement broadly characterized by exoticized portrayals of Asian and North African subjects by European artists. In terms of art historical categorization, Orientalism encompassed a wide variety of styles, techniques, and intentions. Perhaps the most celebrated artist with a predilection for Orientalist subjects was Eugène Delacroix, whose erotic and sensuous depictions of “exotic” realms scandalized art critics and salon-goers. In contrast, Jean-Léon Gérôme (whose work Snake Charmers graced the cover of Edward Said’s canonical 1978 text Orientalism) represented a more academic Orientalist tradition. An accomplished Salon painter working during the latter half of the nineteenth century, Gérôme developed his career during a pivotal moment in Western art history. Impressionism was taking center stage as the École des Beaux-Arts and the French Academy were rapidly losing relevance in the art world. Gérôme’s practice, built upon a traditional emphasis on precise draftsmanship, inevitably found itself at odds with these shifts.

Gérôme was known for his meticulous naturalism, clean execution, and obsessive attention to detail. His early years in the Academy were defined by an association with the Neo-Grec movement, a Neo-Classical revival that concentrated on Greco-Roman subjects. These early compositions revealed certain qualities that would remain dominant throughout Gérôme’s career, most noticeably in his quest for incontestable accuracy and objectivity. The artist fortified these paintings with archeological exactitude, studying antique vases and sculptures for inspiration, and even commissioning reproductions of ancient costumes for his studio models to wear. Soon, Gérôme became famous for his application of this detail-oriented style to North African and West Asian subjects.

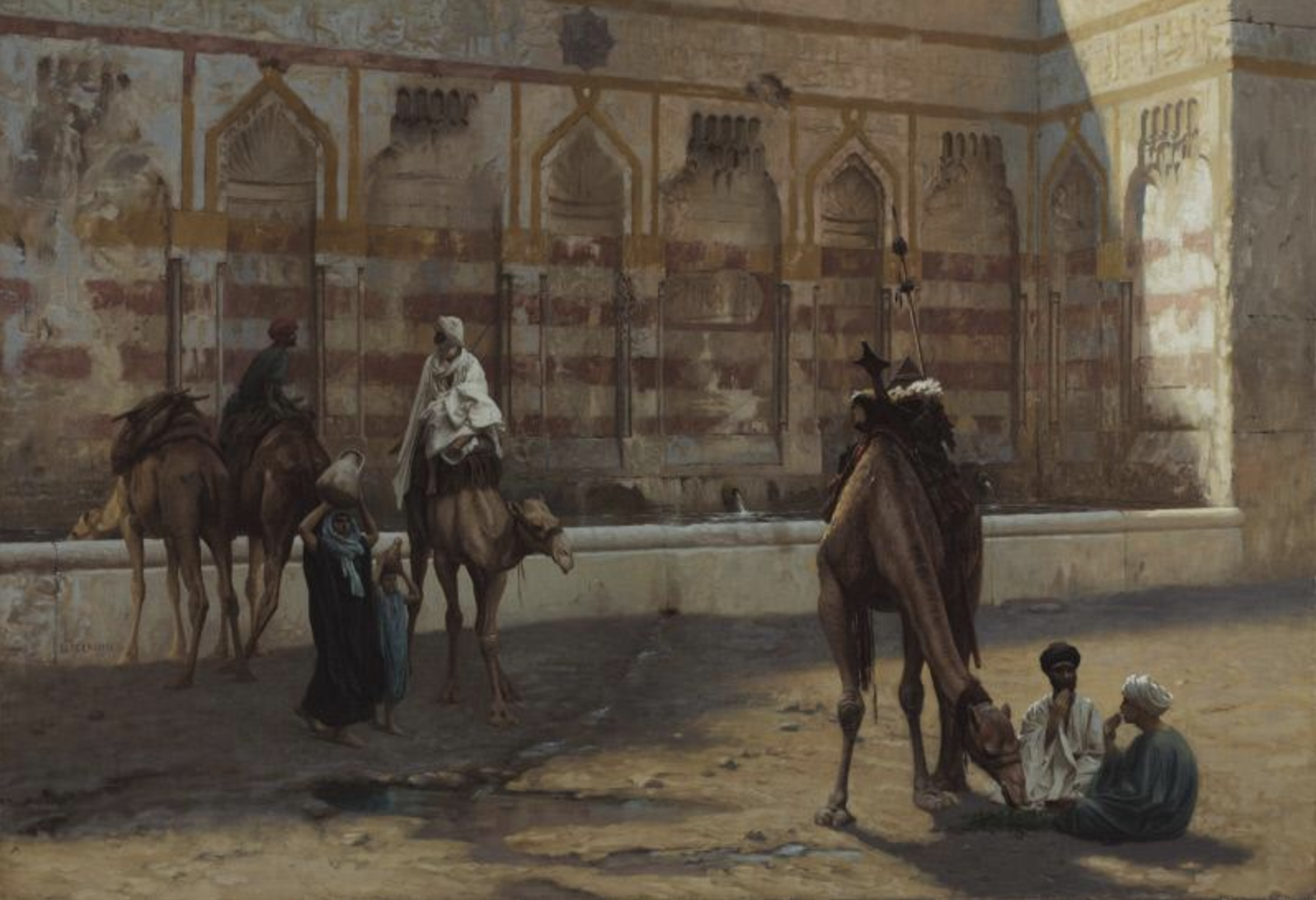

Throughout his career, Gérôme frequently took trips to North Africa and Turkey, leading caravans throughout the region, bringing along various traveling partners. The artist documented these travels in his sketchbooks, bringing back to France an extensive portfolio of figure studies and architectural drawings. Gérôme would later dip into this reservoir of sketches for works executed in his Parisian studios. First-hand experience and detailed study of North Africa and West Asia allowed Gérôme to claim a semblance of objectivity for his Orientalist paintings. His style was supposedly documentary, ethnographic and anthropological; European consumers could receive an authentic taste of foreign cultures and traditions. However, like many Euro-American artists depicting non-Western peoples and places, Gérôme’s paintings inevitably deployed tropes that underlined the otherness of their subjects. Orientalist works were filled with eroticized bodies to be consumed, grossly stereotyped figures, and exoticized fantasy realms. Due to Gérôme’s naturalistic style, it is easy to miss or disregard these motifs—he seems to tell a story as it is, without intervening filters. Of course, this does not mean that the story is true, whole, or remotely objective. In this blog, I would like to enlarge and untangle Gérôme’s story by exploring the identity of this anonymous “Watering Place” he chose to depict.

Gérôme first exhibited Camels at the Watering Place near the tail-end of his career in 1890. As the artist spent relatively little time abroad during this period, his Orientalist works of the 1890s and 1900s relied heavily on the sketches and studies made during earlier expeditions, supplemented by photographs taken by his traveling companions. Though the painting’s title is nonspecific (the original French title was simply L’Abreuvoir, meaning “drinking trough”), its architectural backdrop locates the scene in Cairo. The alternating recesses that punctuate the fountain’s wall use two forms characteristic of architecture in thirteenth to fifteenth century Cairo: a conch half dome and muqarnas (ornamental vaulting that creates a stalactite or honeycomb effect). Both elements were often similarly deployed to decorate the portals of Cairene monuments. Additionally, the alternating pattern of red and white stones represent an aesthetic found throughout the Islamic world, called ablaq masonry. Though in his painting the architecture’s calligraphic inscriptions are likely an illegible imitation of Arabic script, Gérôme convincingly renders the flowing lines of Islamic epigraphy. The figures and camels are rendered in the artist’s precise yet slightly stiff style, their costumes and accessories treated with great detail.

Furthermore, the light effects displayed on the sun-kissed wall behind the fountain are a testament to Gérôme’s tremendous skill with paint. Even though the French master had not visited Egypt for nearly a decade when he completed Camels at the Watering Place, this weathered fountain constitutes a well-executed stage for Gérôme’s Cairene genre scene.

As Gérôme’s title for the painting was generic, the precise identity of this anonymous “drinking trough” had never been ascertained during the seventy-five years it has been at Vassar. Incredibly, in 2014, two architects from the Cairo-based firm ARCHiNOS perhaps rectified this gap in our knowledge. The firm had been employed to restore the Funerary Complex of Mamluk Sultan al-Ashraf Qaitbay, and the two architects proposed that the structure in Gérôme’s painting was the hawd (a public water trough for animals) still connected to this monument; they contacted the Loeb to ask for permission to use the image in their publications. Although the artist’s rendering is not perfectly identical to the surviving hawd, the resemblance is certainly convincing. Beyond its pertinence to the painting at hand, this anecdote demonstrates the value of plurality in academia—of welcoming new voices into our established narratives. Investigating the identity of Gérôme’s subject permits us to expand this story beyond the frame that the artist provided, and acknowledge the life and autonomy of his unlabeled water trough.

When Gérôme visited Cairo in the nineteenth century, the city was already a tour de force of Islamic architecture, containing buildings and monuments from successive dynasties spanning more than a millennium. At the time, Egypt was controlled by the dynasty of Muhammad Ali, an Albanian military commander appointed viceroy by the Ottoman Empire. The hawd in Gérôme’s painting dates to the Mamluk Sultanate, a regime that controlled Egypt and parts of Syria for nearly three centuries before the Ottomans conquered the region in 1517. Though the Mamluks had entered Egypt as military slaves under the Ayyubid dynasty, they quickly rose to prominence, becoming some of the most prolific patrons of art and architecture in the medieval world. Mamluk sultans greatly impacted Cairo’s cityscape, most noticeably with the proliferation of grand multifunctional complexes that fused public services (such as schools and water fountains) with mausoleums and mosques, among other features. As ARCHiNOS proposed, the hawd depicted by Gérôme is connected to one such structure: the Funerary Complex of Sultan Qaitbay, built between 1472 and 1474.

These Mamluk complexes embraced a rather distinctive conception of monumentality, as charity and community engagement were integral to their design. By the late fourteenth century, one nearly ubiquitous element in these structures was the sabil-kuttab: a two-story building that contained a sabil (drinking fountain) and a kuttab (Qur’an school). The former supplied free drinking water to city dwellers, travelers, and pilgrims on their way to Mecca; the latter provided free primary education to orphan boys. Sultan Qaitbay’s hawd was similar to the sabil, supplying free water to pack animals rather than people. The construction of these charitable structures was considered an essential act of piety, a means of serving the Islamic community. Mamluk monuments were thus expressions of faith, as well as conspicuous displays of wealth and authority.

By the time of Gérôme’s visit, the surviving vestiges of Mamluk power had been completely eradicated: in 1811, Muhammad Ali had massacred all remaining Mamluk officials, who had retained significant power under Ottoman rule. Thankfully, their legacy was forever enshrined in their monuments—yet, as Gérôme illustrated in Camels at the Watering Place, many Mamluk buildings were clearly showing the wear of age and use. However, the story of Sultan Qaitbay’s hawd does not end with the Mamluk massacre—nor with Gérôme’s painting. The structure continues to hold power and breathe life, as shown by the ARCHiNOS restoration work finished in 2015. Not only has the monument been preserved, but also it was planned that artisans practicing traditional crafts would be able to display their products in the restored hawd, allowing the building to once again serve the community.

It also seems that the life of Gérôme’s Camels at the Watering Place has expanded beyond its initial bounds, because ARCHiNOS has placed a detail of the painting on their website, alongside a description of their work on the hawd. For me, this placement was an extremely powerful statement. Not only does ARCHiNOS give Gérôme’s painting the context that it desperately needs, their use of this image is an act of repossession—a way of saying, “This is not ‘Camels at the Watering Place.’ This is the hawd of Sultan al-Ashraf Qaitbay’s Funerary Complex.”

Image from ARCHiNOS website: https://www.archinos.com/conservation-of-the-hawd-of-sultan-qaitb